The name José Luis Díez will be familiar to those with a knowledge of Gibraltar’s history, but less so elsewhere. This Republican ship, which could be described as ‘lucky’ or ‘ill-fated’, depending on one’s point of view, caused diplomatic ructions with the Gibraltarian and British authorities after seeking refuge on the Rock after being damaged during a battle.

José Luis Díez is a Spanish name which has become part of Gibraltarian history, although it is little-known outside the Rock. In fact, this particular José Luis Díez was not a person, but a ship, a Churruca-class destroyer from the Spanish Republican Navy, which was being used in the Civil War on the government side.

Should we describe José Luis Díez as ‘lucky’ or ‘ill-fated’? Few vessels can have had such a chequered history. She was involved in battles at sea and was holed but did not sink; she was saved by the generosity of Gibraltarian dockyard workers and then deliberately beached in Catalan Bay after a brave, although some might say foolhardy, attempt at escape.

The design of these ships was so similar to the British Scott class that confusion sometimes arose. This part of the story began when the José Luis Díez was disguised as a British destroyer (she was painted with the pennant of HMS Grenville and flying the Royal Navy flag) to try to break the Nationalist blockade of the Strait of Gibraltar and reach the Mediterranean.

After two frustrated attempts she tried again, became involved in a battle and was holed. The damage was so severe that she was forced to seek refuge in Gibraltar. This was on 27 August 1938.

The presence of a Republican ship was a great embarrassment to the Gibraltarian authorities, because of Britain’s pact of non-intervention in the Civil War. Also, the British and Gibraltarian authorities were sympathetic towards Franco. There was a great deal of diplomatic to-ing and fro-ing as they tried to decide what would be the best thing to do. In the end they decided she would have to be repaired by the crew and that this should be done as swiftly as possible to put an end to the problem.

However, this was not as simple as it sounded. The damage was too severe for the crew to fix. Someone else would have to do it. The British authorities would not allow the ship to be repaired in the Naval dockyard and were even reluctant to give permission for the crew of approximately 180 men to disembark. As Dr Gareth Stockey reveals in his book ‘Gibraltar, A Dagger in the Spine of Spain’, local shipping agents refused to work on the ship, claiming that doing so could jeopardise their business interests in Nationalist territory in Spain. In 1936 they had also refused to supply oil to the Republican fleet, despite doing so on the Nationalist side.

However, Gibraltar at this time was very divided and among the working class in particular there was considerable support for the Spanish Republic. The presence of the stricken vessel and its crew aroused strong feelings of sympathy and support among many – but by no means all – of the dockyard workers, and they decided to carry out the repairs themselves, unpaid.

In his research for his book Our Forgotten Past, George Palao noted that the José Luis Díez was moved to a less visible position in the harbour and the 8ft hole in her side was covered with tarpaulin so that spies, such as Nationalist sympathisers and Spanish workmen who came into Gibraltar daily, couldn’t see how the repairs were progressing.

They took several months to complete, but by the end of December the José Luis Díez was ready to leave, much to the relief of the Gibraltarian authorities. She sailed out under darkness, in the early hours of 31 December. Most reports say she crept out stealthily, leaving somebody holding a light up at her normal position in the harbour to make it look as if she were still there, but George Palao says this was refuted by a crew member he met many years later. This sailor told him the ship had had to leave, under orders from the Republican government. The captain had asked to wait until other Naval ships were sent to the area to provide assistance, but was told they were already on their way and he was to go. Those ships never arrived.

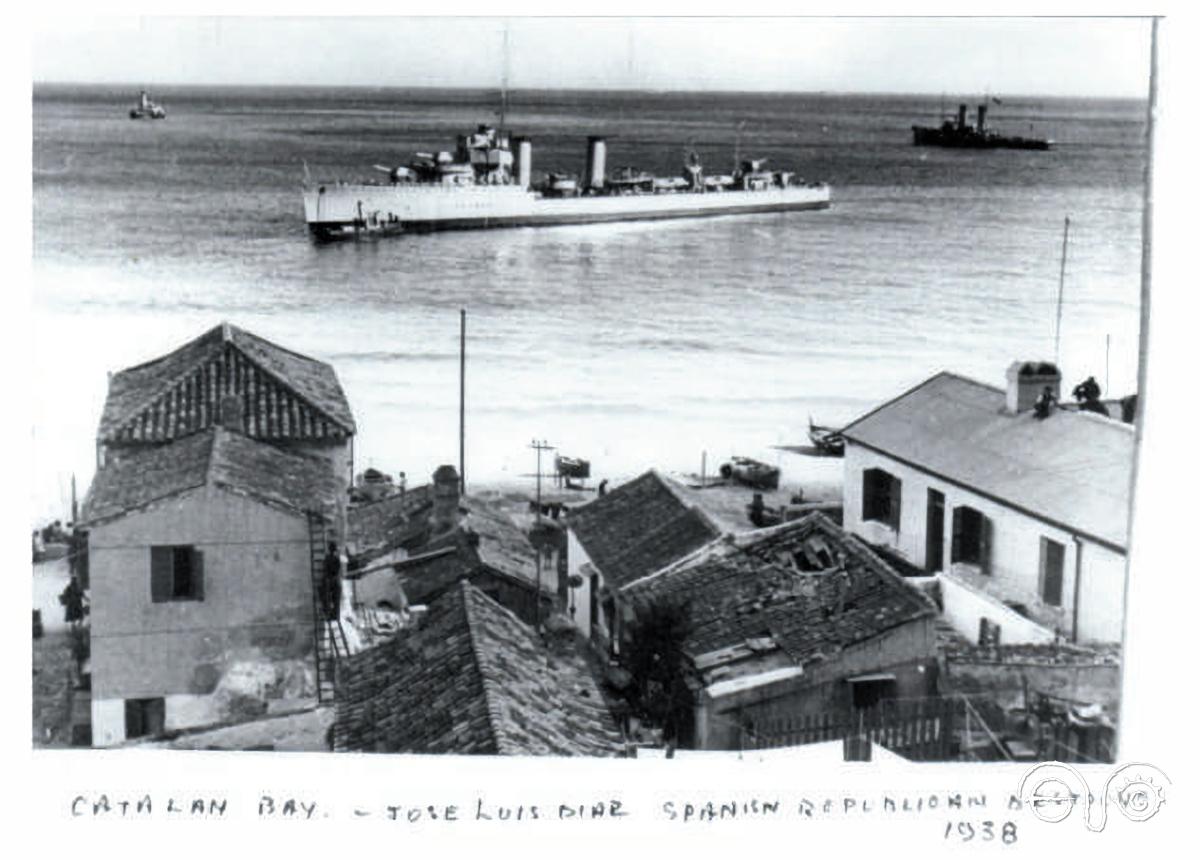

The crew member who spoke to George Palao told him the ship was travelling fast as she headed out to sea, but the Nationalist forces knew she was coming. Someone in Gibraltar had set off a flare – probably more than one – to alert them. She was attacked by several of their ships about ten miles off Catalan Bay, and during the ensuing battle she collided with one. Despite only having one gun against these considerably superior forces, she continued to fight until a shot into the engine room caused the main steam pipe to burst and she lost speed. The captain then ran her aground at Catalan Bay, still under fire from the Nationalist ships. Some of the shells fell on the Village, damaging roofs and buildings and injuring a number of people.

The captain used a loudspeaker to call for assistance in removing the dead and wounded members of his crew and the villagers set off in boats to bring them onshore. A military guard was placed on board the ship and its flag was struck. The captain was held under guard, and when asked why he had made the escape attempt with such odds against him, he replied “It is better to have honour and no ship, than a ship and no honour”.

The crew were repatriated to Spain. They were asked individually where they wanted to go and, unsurprisingly, none of them wanted to go to the Nationalist zone. They were transported to Almería on board two British destroyers.

The José Luis Díez’s fighting days were over. In March 1939 the British government handed the ship over to the Nationalists, and in 1965 she was finally decommissioned and scrapped.